“College costs too much!”

“My college loans are killing me!”

The candidates for the presidency are hearing these complaints as they race around the country. Affordability of a college education is among the few education issues to attract attention in this election season.

Colleges and universities are blamed for the high costs resulting from not controlling expenses. Less well-known is that state governments by reducing their support of public colleges and universities are also culpable for increasing the burden of loan indebtedness.

The complaints about rising costs are accurate. In public degree-granting institutions, which educate about three-fourths of the country’s undergraduates, tuition and fees are 3.22 times their level of 30 years ago after adjusting for inflation.

The only good news for students and parents is that costs are not accelerating over time. The inflation-adjusted increase in the last decade was smaller than in either of the previous two decades.

Assuredly colleges and universities must continue to control costs. But, the other side of the ledger is less discussed. Who is paying for those higher costs?

In 2007-08, states provided about 24% of the revenues of four-year public institutions; but, by 2013-14, that support had declined to less than 17%. During the same period, tuition and fees at these colleges and universities rose from about 18% of revenues to about 21%.

Those two trends are connected. Tuition paid by students is higher because state support of post-secondary education is lower.

“…(T)he failure of state funding to keep up with growing enrollments, a key factor in pushing tuition up,” was noted recently by the College Board. Enrollments have increased dramatically—30% in the fourteen years between 2000-01 and 2014-15. Institutions needed greater funding to meet the needs of their larger student bodies. That support was not forthcoming from the states. Therefore, colleges and universities charged students more for tuition.

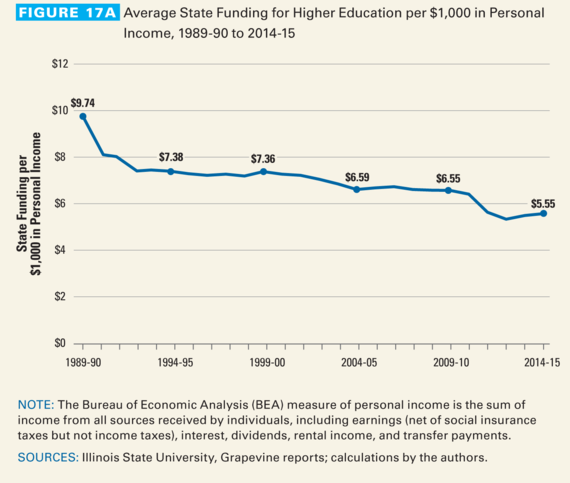

Another way to consider the state role in funding is to look at the proportion of state revenue going to colleges and universities considering the personal income in the state. “The proportion of state resources going to support higher education, measured by funding per $1,000 in personal income, declined from $9.74 in 1989-90 to $7.36 in 1999-00, to $6.56 in 2009-10, and to $5.55 in 2014-15,” according to the College Board which included this figure in its recent report, Trends in College Pricing 2015 (page 28).

In other words, over time, states have not placed the same emphasis on funding colleges and universities as they had before. Other ideas influenced their budgeting, such as reductions in state taxes.

For years, conservative “think-tanks” have argued that those who get bachelors’ degrees are the beneficiaries of that education, and so they should bear the burden of paying for it. Other people who didn’t get a college education should not have to pay taxes to support the institutions providing that education or the students working for a degree.

This argument has been persuasive with state governors and legislatures as they have become more conservative during last few election cycles. That reasoning, though, ignores some basic facts.

First, students who work, an increasing percentage of the student body, pay taxes, as do the parents of college students. Shouldn’t they have some say in how their taxes are spent?

Another important reason to support post-secondary education is that it benefits society and the economy to have more people who are better educated. For instance, better educated people are healthier and therefore not as likely to be absent from work because they are sick. They will also require less health care and therefore will be less of a strain on hospitals and insurance companies.

The economy also gains from having more college-educated workers. Today, the shortage of college-educated workers is holding the economy back from greater prosperity which would benefit everyone. A Georgetown University report estimates that $500 billion a year is lost because more Americans have not attended college.

Governors and state legislatures would be wise to invest in post-secondary education for the social and economic good of their states. Instead, students and parents have to take out more loans to pay for college.

The total outstanding debt from these loans has nearly tripled in ten years. In 2004 the amount was $435 billion, and by 2014 it had ballooned to $1.6 trillion.

That indebtedness is a drain on the economy since students will have to pay down their loans when they finish college, leaving less to spend on cars, condominiums, and furniture.

If post-secondary education is to become more affordable for students and parents, the equation will have to change again. This election season shows indications that a reversal from a smaller state role and a bigger dependency on loans may occur with the new president.

Senator Bernie Sanders has proposed making an education at a state college tuition-free. Hillary Clinton offers a more modest proposal to lighten the costs. While their proposals are based mostly on greater federal funding, both envision the states providing more support for post-secondary education than they are doing presently.

Interesting in how the wheel turns. But, whether that happens will be the voters’ decision.

Do we think that anyone wanting to be better educated should pay the costs from their own resources? Or, do we believe that we as a country are better off when more people are educated?

This article first appeared as a blog by Jack Jennings on the HuffingtonPost on April 26, 2016.